I was a guest recently on Something is Going to Happen, the preeminent blog of Janet Hutchings, editor of Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. I share the post with you, below, and you may also click here to view the entire post with Janet’s comments. Mystery lovers: take the time to scroll through the blog entries on the site: some interesting articles!

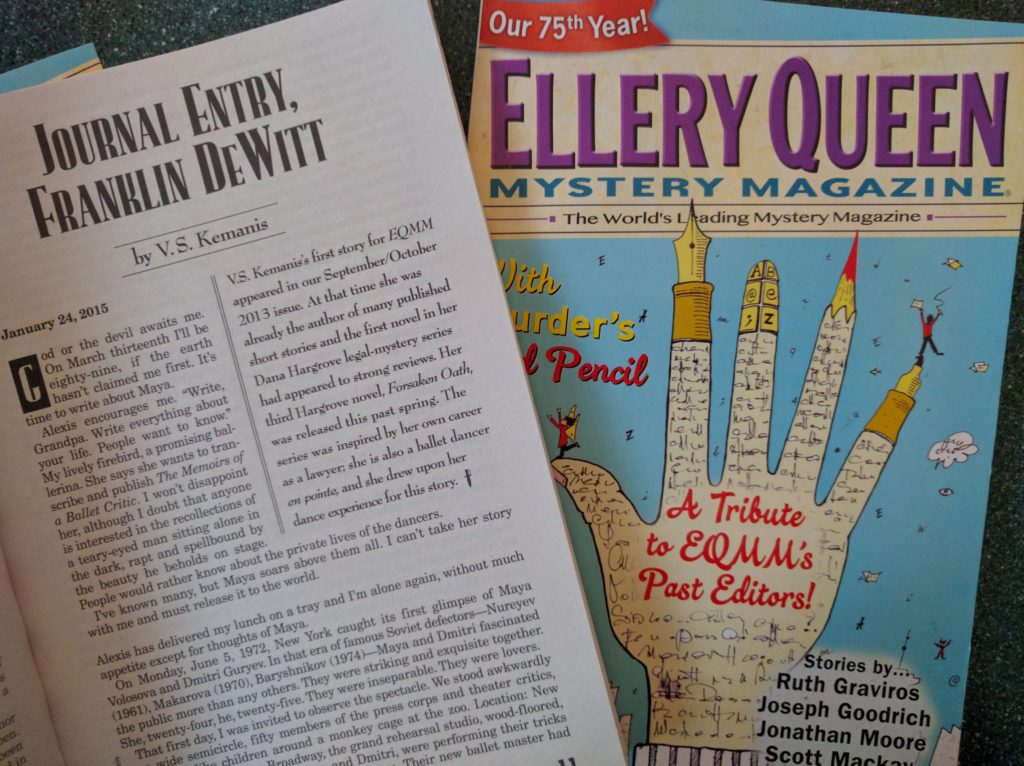

Also, check out the exciting July issue of EQMM. My story, “Journal Entry, Franklin DeWitt,” will appear in the August issue!

Ballet, Law, and Mystery

Before writing fiction, I was a dancer and a lawyer. Still am, both. Oxymoron? You’d be surprised how many attorneys I meet in ballet class. Maybe it’s because law books and toe shoes are both hard—dancing attorneys are gluttons for punishment. On a positive note, ballet and the law share many nicer attributes. An idealized world, perfectionism, intellectual puzzles, exacting discipline, technical precision, and personal expression. The expressive medium of ballet is the more artistic, you might say, but I could debate the point (sounding like a lawyer here, even if we swap “point” for “pointe”).

My experience in the courtroom informs my fiction more often than my experience in the dance studio (although the protagonist in my novels, prosecutor Dana Hargrove, does take a weekly dance class with her sister Cheryl, a Broadway performer). With pleasure, I dove into the world of professional ballet in writing “Journal Entry, Franklin DeWitt,” for EQMM. Memories from the time I owned a dancewear shop came in handy for this story. It could take hours fitting those potential instruments of torture, pointe shoes, on the feet of persnickety ballerinas—always a Cinderella-esque exercise in frustration.

As for this blog piece, I thank Janet Hutchings for humoring my obsession and allowing this small offering, a short-short mystery. The style is not my usual, but like every word buff, I look for any excuse to have fun with language—here, the beautiful language of ballet. Consider, for example, this direction for a lovely petit allegro enchaînement: “Glissade précipitée en avant, temps levé, tombé, saut de chat.” If the ballet instructor were to say it like this—“Quick steps forward, hop, fall, and leap like a cat”—I might just walk out of class.

You will find, at the end of the story, a glossary of the less obvious ballet terms.

Doctor Coppélius Meets an Untimely Death at the Opera House

As the only child of two physicians, Sylvia Musette was destined for a future in the healing arts. So it seemed, until destiny took a detour on the occasion of her eighth birthday, when she was treated to a matinee at the National Ballet. From that moment, every step she took was a chassé toward her dream.

At seventeen, she signs with the company. Passion is no guarantee of talent, and Sylvia’s passion falls short of artistic distinction, her grand jeté an inch below soaring, her port de bras heartfelt but uninspiring. Ever hopeful, she languishes in the corps, one of many cygnettes, sylphs, and Wilis.

In her fifth spring season, the light of good fortune shines upon her. Ballet master Stanislav Gliadilev, towering over the diminutive Sylvia, twirls a waxed end of his mustache and declares: “Friend!” She fights to remain à terre. It’s her first supporting role! One of Swanilda’s six Friends in the comic ballet Coppélia. Her heart nearly sautés from her leotard before the impresario qualifies the offer: “Understudy!” Sylvia wilts.

An exhausting rehearsal schedule fails to wilt Les Amies, who remain remarkably healthy and uninjured while Sylvia shadows them, unnoticed, a fly on the studio mirror. With too much time on her hands, she is, quite unintentionally, on a gradual pas de bourrée couru toward her true calling in life. Nothing escapes her eye.

She studies the principals: prima ballerina Peony Torne in the role of Swanilda, Enrique Dagloose as her fiancé Franz, and Morton Avunculario as Doctor Coppélius. Peony is known for the delicacy of her petite batterie, Enrique for his ballon, and Morton for his danse de caractère. What is the secret of their success? They’re strong and beautiful, Morton the most powerful, a favorite of Gliadilev who always gives him what he wants. Fifteen years older than the others, Morton is made to look 85 on stage with a painted face and a wig of scraggly gray hair, stooped and teetering with the aid of a cane.

Hmm, Sylvia thinks, did this help Peony make it to the top? Perhaps if I cozy up to Morton the way she does, gazing droopingly at him while Enrique scowls with glints of daggers in his slitty eyes . . . ? The whole thing is backward from the story in the ballet. Swanilda isn’t attracted to that crotchety, diabolical inventor, Doctor Coppélius, a disturbing figure with a toyshop full of spooky, life-size mechanical dolls. And Swanilda is the jealous one, not the faithless Franz. He’s duped and smitten by the lifelike doll Coppélia, sitting on the balcony of the toyshop, reading a book.

On the eve of opening night, an hour before full dress, company class is held on stage with portable barres. Peony, Morton, and Enrique plié center stage, and the others fan out from center, the Friends, the Dolls, the townspeople, and finally the understudies, lining the dark edges. Sylvia is a useless appendage, she feels. At least she would like to observe the greats, but they’re barely visible behind all the bodies executing les exercices à la barre: tendus, dégagés, ronds de jambe and finally, battements en cloche.

A small commotion erupts. Rats! What’s happening over there? Enrique mutters something to Morton, who gives an audible harrumph and stumbles away in the hunched posture of Doctor Coppélius, hand at the back of his neck. The dancers disperse to dressing rooms, wishing each other “merde.” The maître de ballet spies the understudies and shrieks: “Get off the stage!” In the midst of chaos, Sylvia slithers behind a wing, unnoticed.

Second act, it’s the dead of night, and something is astir, a menace of unknown origin. Swanilda and Friends break into the toyshop, setting the mechanical dolls to life. The Troubadour executes a stiff tour en l’air, the Spanish Doll a sharp coupé fouetté raccourci, the Scottish Doll a nervous pas emboîté en tournant. The Doctor bursts in! Friends scatter, Swanilda hides, Franz sneaks in through a window and is caught! Intending mockery, Doctor Coppélius produces two tankards, and they drink heartily to Franz’s love for Coppélia.

Franz is passed out when Swanilda appears, impersonating the mechanical doll Coppélia. But the Doctor is not quite himself. Deathly pale, he staggers off stage, totters and collapses behind the façade of the toyshop. With a brisk brisé volé, Swanilda runs to him. The music stops. “Morton, darling!” She cradles the gray-wigged head in her lap and looks up, searching blindly. “Please, somebody, help!” The Doctor needs a doctor. The maître drops to her knees, frantically feeling for a pulse. It appears that Morton est mort.

From center stage, Gliadilev quiets the crowd. “Remain calm! I’ve called for an ambulance.” From behind the curtain, Sylvia discerns, in the tensing of muscle, the pain that the impresario feels for the loss of his friend. Or maybe he’s remembering the inferior quality of Morton’s understudy. Opening night will be a disaster.

“How can this be?” The tear-stained Peony stands, bras croisé, mindlessly stabbing piqués en croix with her right foot. “There!” She points to the tankards. “He’s been poisoned!” She whirls in renversé. “He did it!” Enrique is fingered. But Peony pirouettes anew, unable to make up her mind. “No . . . it has to be him!” She points at the mousy little props man, scratching his head in confusion.

“Wait! You’re wrong.” Sylvia chaînés swiftly out from the wing. Quickly, before Gliadilev can banish her, she grabs the tankards, one at a time, and drinks from each. “It’s water.” She licks her lips. “Maybe a bit of iron oxide.”

Dumbfounded, the company awaits Sylvia’s next move. Like magic, a path to the body is cleared. Sylvia kneels, removes the wig, and palpates gently. “Basilar skull fracture, occipital bone, subdural hematoma likely. Suffered a blow with a blunt instrument. He’s been dying slowly before our eyes.”

There’s a communal gasp amid darting, wary glances. Was it the Troubadour’s lute, the Scottish Doll’s bagpipes, the Spanish Doll’s fan, or that little hardcover book Coppélia was reading? Maybe the assailant used the Doctor’s own cane, or a dismantled section of the barre? Sylvia examines the shape of the injury, mentally calculating height and velocity. She stands to face Enrique, his head drooping en bas. For weeks now she’s been studying him, getting to know every habit and quirk of technique. “You were standing behind Morton at the barre. It was your battement en cloche, wasn’t it? Directed straight to that nice little groove between neck and skull.”

“But,” Enrique protests, “I didn’t mean for him to die!” The suspect attempts an échappé sauté, but Gliadilev seizes him before he can run.

Intentional, reckless or negligent? A question for another day, a question for a jury. With a joyful sissone fermé, the case, for now, is closed. Sylvia is arisen from the corps.

A Literally Figurative Glossary of Ballet Terms

ballon: lightness, the ability to remain suspended in the air.

battements en cloche: beats like a bell. Basically, you swing your leg front and back, very high, like the clapper of a bell; it’s fun and relaxing.

bras croisé: arms crossed.

brisé volé: broken, flying. A beautiful light step with a small beat of the legs.

chaînés: chains, links. These are fast turns in a line, spotting your destination. Really fun to do and a good way to get dizzy if not done properly.

chassé: chase. Slide forward, one foot chasing the other.

coupé fouetté raccourci: literally cut, whip, and shorten. Does this give you any sense of what it looks like? Too difficult to explain.

échappé sauté: escape leap. As you jump, the feet “escape” from fifth position into second.

merde: I don’t need to tell you what this really means. It’s a dancer’s “good luck” wish.

pas de bourrée couru: a series of tiny rapid steps on pointe. When ballerinas look like they’re floating across the stage, this is what they’re doing.

pas emboîté en tournant: a springy, boxed-in step in a circle.

petite batterie: small battery in the sense of beating. There’s a lot of beating in ballet terminology, although it’s far from a violent art form.

piqués en croix: sharp piercing taps with the toe, front, side, back, in the shape of a cross.

renversé: reversed. You wouldn’t think this word is enough to describe the actual movement. It’s a turn with a pitched body and a high, circling leg.

sissone fermé: a leap from two feet into a split, landing on two feet in a closed position.

tour en l’air: turn in the air. Jump straight up, do a full revolution like a pencil, and land. Harder than it looks.

ormer managing editor of EQMM), and award-winning authors Jonathan Santlofer, Joseph Goodrich, Josh Pachter, and Charles Ardai.

ormer managing editor of EQMM), and award-winning authors Jonathan Santlofer, Joseph Goodrich, Josh Pachter, and Charles Ardai. nt their new magazine, there could not have been any question that its outlook would be global. Both men had cosmopolitan tastes and a knowledge of world literature. It has become part of EQMM lore that Dannay, who soon took over the editing of the magazine, aimed to prove, in its pages, that every great writer in history had written at least one story that could be considered a mystery.”

nt their new magazine, there could not have been any question that its outlook would be global. Both men had cosmopolitan tastes and a knowledge of world literature. It has become part of EQMM lore that Dannay, who soon took over the editing of the magazine, aimed to prove, in its pages, that every great writer in history had written at least one story that could be considered a mystery.” and its e-book anthology, The Crooked Road Volume 3. I’m also fortunate to have been welcomed into this community of amazing authors. As one of the panelists noted, mystery and crime writers are a really nice bunch of people because we’ve transferred every bit of aggression and nastiness to our fictional characters!

and its e-book anthology, The Crooked Road Volume 3. I’m also fortunate to have been welcomed into this community of amazing authors. As one of the panelists noted, mystery and crime writers are a really nice bunch of people because we’ve transferred every bit of aggression and nastiness to our fictional characters!